Venture Capital is elite, white, and male: how that’s holding American businesses from serving vulnerable communities

When Donnel Baird read the news about the Bronx building fire on January 9—the deadliest one in New York City in three decades—his mind immediately went to his childhood. Like the 17 people who died in the tragedy, Baird once lived in a low-income building with a dangerous and inefficient heating system in New York City.

The January tragedy was tied to an electric space heater, used by a tenant because of the building’s chronic lack of heat. The news struck a chord with Baird because he had grown up using an oven to heat his apartment in Bedford–Stuyvesant, a neighborhood in Brooklyn.

Every winter night, he had to avoid going by the oven and inhaling harmful carbon monoxide and other toxins. His father, a mechanical engineer, taught six-year-old Baird how to turn on the oven and also to prop the window open with a wooden stick for the toxins to flow out. As a child, Baird urinated in a bucket during cold winter days because the oven was on the way to the bathroom – an open stove was too dangerous for a child to pass through.

Today, he is a successful entrepreneur, who raised over $100 million to fund a business that is focused on making old and dangerous city buildings—like the one where he grew up — safer. His startup, BlocPower, converts their heating and cooling systems or HVACs into sustainable electric ones that use solar power, ductless air source heat pumps and smart thermostats.

But getting the company off the ground wasn’t easy; it was hard to get investors excited. Baird found out that most people with deep pockets just couldn’t relate to his experience, the need for this business or how it would make money.

“I spoke to 200 venture capitalists, and all of them said they would not invest,” Baird said, referring to the early days of pitching his idea.

VCs are notoriously white and male – Over 80% of VCs in the US are men and 70% are white according to a 2018 analysis from Richard Kerby, a partner at Equal Ventures, a New York City seed stage venture firm. But the power gets even more concentrated when you break down these numbers by dollars: white men control an estimated 93% of the venture capital.

This gap has cost minorities, whether it’s people of color or women. Many people come up with business ideas based on the needs and opportunities that they see from their own experiences. But when the power centers that hold the purse strings have never had that experience, it’s hard

to grasp the opportunities these founders present.

Baird has a ‘screaming match’ with a VC

Baird knew from his own experience of growing up in communities that were disproportionately Black and Latin that there was a definite need for his product. But investors just couldn’t relate to his vision.

Baird says one VC even suggested he start marketing BlocPower to affluent communities and target poorer areas later down the road. The reasoning was that he could initially charge more for his product and once he had a foothold in the upper class market, he could price it down for a mass market. Baird was enraged by the idea.

“I got into a huge screaming match…We can't do that because the planet is going to burn. We only have nine or 10 years left to make massive changes in terms of climate change. We need mass market products now that are priced that way.” Baird says.

Other VCs questioned whether communities of color even wanted access to clean energy. Baird grew frustrated.

“You have a set of investors who literally can’t imagine that a woman or a person of color can come up with a good idea, much less go out and implement that idea,” the entrepreneur says.

Hyper focus on financial returns versus impact

Baird eventually found investors who were willing to bet on his idea. But these VCs were driven by a mission of social impact.

One of his first investors was Freada Klein, whose fund is the VC investment arm of Kapor Center for Social Impact. Founded in 1999, Kapor Capital is an impact investing firm that has a portfolio of more than 120 companies, and over 100 exits.

She believes that the dearth of diverse founders is not only a fairness issue, but is also a missed opportunity.

“What I think too many VCs miss is that BlocPower solution, and like many others in our portfolio, they bring money… So, it is better for everyone,” the investor says.

Kapor’s portfolio of investments is 59% female and founders of color. Klein says its mission is to fund businesses that close gaps of access or opportunity for low-income communities and communities of color. And because founders tend to search for market solutions to problems they have experienced first-hand, Kapor has a very diverse portfolio.

But funding is dismal for minorities and women overall. In the first half of 2021, Black start-up founders received 1.2% of venture capital invested in US start-ups, according to Crunchbase. Female entrepreneurs received about 2% of all venture funding, according to a report by research firm Pitch Book.

VCs’ implicit biases

Research has shown that implicit biases—when people associate stereotypes toward others unconsciously or otherwise—are pervasive in the pitching process. According to a 2017 study of Q&A interactions, VCs pose women different questions than men. While men are asked more “promotion” questions that relate to their startup’s potential for gains, women are asked more “prevention” questions about risks. The study also found that the types of questions founders are asked directly influence funding decisions.

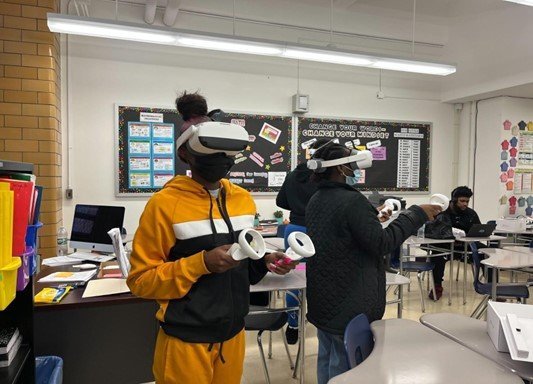

That’s what founder Anurupa Ganguly experienced when pitching her idea in the early part of 2020. She says most VCs were skeptical about her startup, Prisms of Reality, which uses VR to help underrepresented students excel in math.

Ganguly wanted to talk about her product’s potential and her ability to deeply understand the problem her business tries to solve. Instead, VCs focused their questions on the technicalities and minutiae of possible barriers to success.

She thinks VCs feared the world was not ready for her product.

“But the whole purpose of entrepreneurship is that the world doesn’t look like that yet,” Ganguly says. “And the questions that you should be asking are ‘Can you put together the team? Do you understand the market deeply enough? How are you going to grow this?”

Anurupa Ganguly. Photo: Anjelica Jardiel.

Meritocracy versus knowing the right people

Marie Deveaux is the CEO and Coach at High Tides Consulting, a Brooklyn organization that guides women and people of color in their entrepreneurial journeys. She says most of her clients find it so difficult to fund their business with VC that they end up getting their funding from another route. Most of them, she says, end up using commercial means, like going directly to a bank, looking out for loans, grants, or self funding through 401k, retirement savings, etc.

Prisms’ founder Ganguly went through a similar redirection. She grew so frustrated about her interactions with VCs, that she turned to the Small Business Innovation Research program, a federal program that supports early-stage companies in research and development. In less than a year, Ganguly built her team and refined her business model.

An educational game called ‘Pandemic’ comes into being

Ganguly slept as little as three hours a night creating her prototype. She was convinced of her idea, which was based on about a decade of first-hand experiences working in education.

After graduating from MIT with a Master’s in electrical engineering in 2009, she taught Physics and Math in Boston with Teach for America for about two years. She then became an assistant director for Boston’s public schools until 2015. Then, she moved to the NYC department of education.

In 2018, she became the director of mathematics of Success Academy Charter Schools, where she led a team to implement new approaches for teaching math. But no matter how much effort her team put into the curriculum, Ganguly still saw a substantial drop out of young women and students of color in STEM and subsequent poor career outcomes.

“I couldn’t graduate another generation of kids where I know they’re not prepared for the workforce,” Ganguly said.

She observed how young people learn experientially—through seeing, moving, and interacting with their environment.

“It’s not that the students don’t have [an] interest. There was nothing that was created for them in terms of [an] environment that allowed them to understand whether they were interested or not in math,” the entrepreneur said.

She decided to create the virtual reality learning tool to help kids work with real-life scenarios and develop mathematical models to solve them.

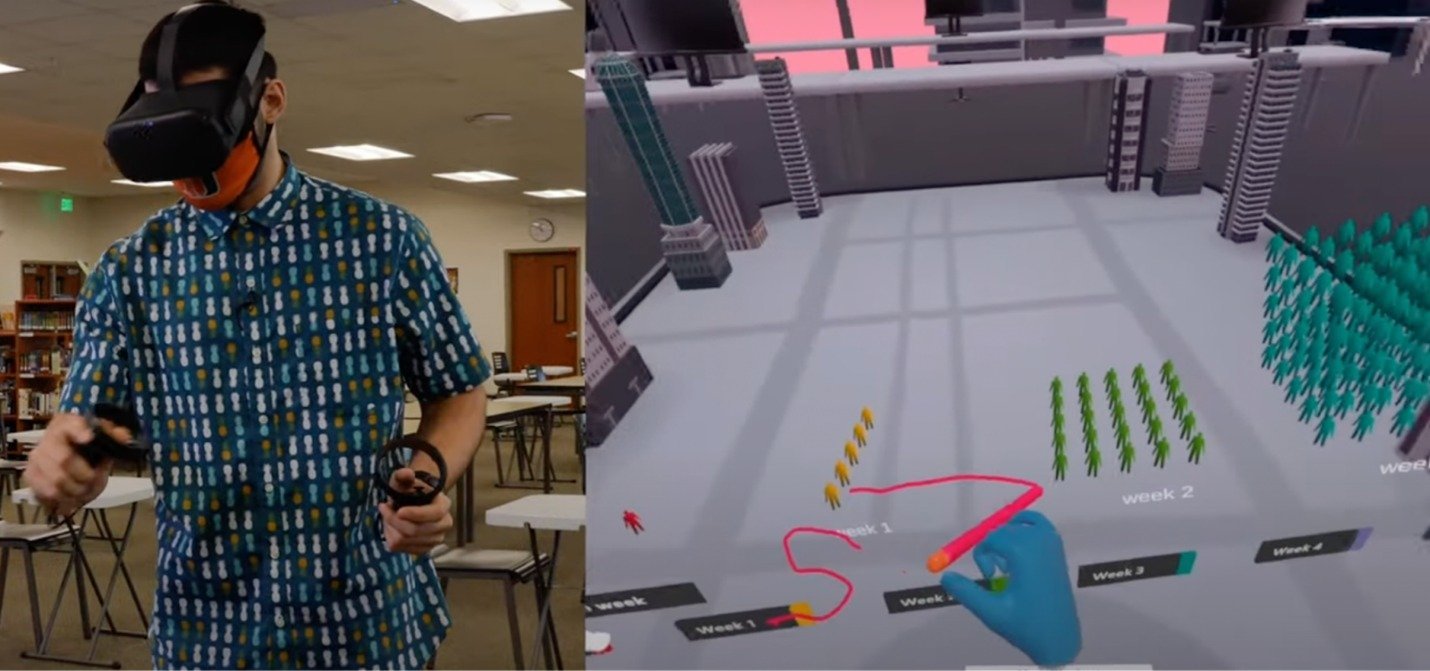

One of prisms’ main products is the educational game, ‘Pandemic,’ which is a simulation of the mathematics of a viral outbreak. In it, kids use VR headset equipment to see how their actions led to the spread of a virus and use arithmetic solutions to curb its spread.

“It’s not intellectual. They’re physically experiencing it,” Ganguly said.

Students try Prisms of Reality’s educational game. Photo courtesy of Anurupa Ganguly.

After completing the federally funded small business program, Ganguly decided to go back to the VC route and, this time, formally pitch.

“My credibility was questioned. Every day was demoralizing,” Ganguly said. “I saw male counterparts with way less than what I had, [and they were] able to raise money,” Ganguly said.

After some rejection, she found her first institutional investor WXR, a female-led VC fund that invests in women at the intersection of spatial computing and artificial intelligence. From there things started to pick up.

“I think had they [WXR] not taken that first bet, I would have had way more difficulty raising,” the entrepreneur said.

A self-fulfilling prophecy

At the early stages of pitching there is not much of a track record first-time founders can use to support their idea and their potential. That’s when implicit biases are most evident.

“Seed investing and pre-seed investing is and always will be a person-driven business. If it’s an idea on a napkin, you’re just betting on people,” says Andrew Chan, the associate at Builders VC.

Vinny Puji, a managing partner at Left Lane Capital, a New York-based VC firm, thinks early stage rounds reveal faulty archetypes:

“A really energetic, high-confidence, somewhat arrogant guy is probably going to be able to raise a huge amount of capital at a very high valuation, just because investors have now created a false connection in their mind [that] founders who talked like this, who looked like this, [and] who have this background are going to be successful,” he said.

American investor and former CEO of Reddit, Ellen Pao, thinks these pattern-matching strategies can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“They [VCs] only invest in a certain type of person. And that demographic is the one that’s successful because it’s the only thing that they invest in, and to them, that’s proof that the pattern works,” she said.

Where are all the women? One VC shares her ideas

Jenna Bryant, is a General Partner and Co-Founder at Embedded Ventures, an early-stage deep tech VC fund based in Los Angeles. Originally from Alabama, she was introduced to the VC ecosystem at 22, when she worked as a tech recruiter, helping pair early stage startups with engineers. That’s when she began to cold outreach people across the industry.

“Literally everything that I've been able to achieve throughout my decade in Tech has been through launching those connections for myself,” Bryant says.

Early in her career, she searched for other women for inspiration. “Sadly, there weren't many,” In most of the firms she worked in, she was the only woman. “Until I started my own, I was the only female,” Bryant says.

In 2018, Bryant became a partner at early-stage hard tech VC fund Riot Ventures. Two years later, she co-founded the Embedded fund, which focuses on space operations, digital engineering, and built a first-of-its-kind partnership with the United States Space Force.

Despite her success, Bryant notices that she is treated differently from her male peers, and often finds that some men don’t even take her seriously.

“I've been cat-called walking through very successful offices. I've been overlooked for board opportunities,” Bryant says.

Jenna Bryant. Photo: Bradford Rogne.

Bryant thinks the heavy lifting of expanding funds’ networks often falls on the shoulders of a few diverse team members.

“If only the diverse team members are doing that work, and there's only one diverse team member, but a team of 11, then it's not good enough,” she says.

It could be different

Donnel Baird is proud of his accomplishments, and at times he is surprised with the impact of his work.

“When you grow up poor, you aren't taught that you can change things. You're taught that you can't change things.”

But BlocPower is now creating a tide of impact. Baird has raised over $100 million– $5.5 million from Bezos’s Earth Fund. $30 million from Bill Gates’ climate Fund. His work received the attention of people like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. The startup delivers clean energy solutions, and employs people from some of New York City’s poorest neighborhoods.

Stories like Baird’s highlight how the types of solutions in the $210 billion industry—the estimated annual US venture funding—are of interest to people across the country.

Freada Klein, the BlocPower investor from Kapor Capital, thinks the ecosystem tends to sideline her efforts as an impact investor. When asked how she responds to those who don’t take her approach seriously, Klein replied without pausing:

“Why don't we look pejoratively at Venture Capital firms that have one and only one metric? And that's financial returns. Isn't that “greed only” investing? And isn't that phenomenally limited?”